Papa’s Glasses and the Tyranny of Knowledge

By Ariane David PhD

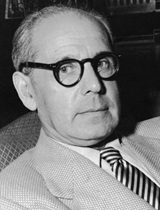

Dr Constantin David

When I was growing up we lived in the rear of a language school that my parents ran and in which they both taught.

My father’s office was on the left just beyond the foyer of the large old Victorian house that had been a language school for so many years and the home of a wealthy family for so many years before that.

I came home from school one day and passing my father’s office I looked in.

Stacking optical lenses.

I saw him as usual seated behind is large wooden desk, his back to the window, the cat to one side sleeping on a stack of papers. In front of him were a pair of glasses, his extra pair, and a number of round glass lenses that might have come from a camera.

I watched as he took two lenses put them together and held them up to his eye. He added a third and did the same. Over and over again he repeated this process using different combinations.

First and Foremost, He Was a Thinker

Lenses stacked together.

Finally, apparently satisfied with one of the combinations he taped the stack of lenses together around the edges with white bandage tape. With more tape, he stuck them to the frame of his extra pair of glasses. He put them on and stood up.

He went to the book case, reached for a book and put it back, reached for another and put it back, too. He went to the kitchen, poured water into a glass and poured it out again. He returned to his desk, reached for a pencil in the middle of his pencil cup and returned it to the very same spot.

He walked around with this odd thing on his face for two days. At the end of that time he announced that he had found the answer. He placed the assembled glasses into his briefcase, put on his eye patch, and left the house.

He Had Found the Answer

I had never known my father without glasses, but a couple of years earlier he had started wearing an eye patch that he switched from eye to eye every few hours. I never understood why, although it had something to do with his eyes no longer working together, so he saw two of everything.

I had never known my father without glasses, but a couple of years earlier he had started wearing an eye patch that he switched from eye to eye every few hours. I never understood why, although it had something to do with his eyes no longer working together, so he saw two of everything.

But, he assured me, they worked just fine separately if he used them one at a time. His ophthalmologist had told him that there was no solution to the problem except to wear a patch over one eye.

For all the things my father had done in his life, he was first and foremost a thinker. He thought about social justice, the origin of words, the evolution of music, and how the soul and subtleties of light and color could be reproduced on a canvas.

In Europe he had been a documentary film maker, which led to an interest in cameras and lenses. Of late, his interest had turned to finding a way to design a three dimensional movie projector.

No Problem Does Not Have a Solution

It was the latter that inspired him to seek his own solution to his double vision. He had some knowledge of optics and lenses but no knowledge of ophthalmological principles.

Medical science had told him that nothing could be done for his eyes, yet he was not constrained by the boundaries of their knowledge.

He used to say that there was no problem that did not have a solution if one were willing to forget what he knows and change his thinking.

Problem Solving and Our Creativity

The contrivance on his glasses was his answer to seeing double. From the taped-together stack of lenses the optician was able to derive an optical formula and grind a single lens for each eye. My father never wore a patch after that, only thick glasses.

Several years later, he was asked to speak at an ophthalmological conference where he explained to the assembled physicians what had inspired him to seek a solution to a problem they believed had no such solution.

The way the brain handles knowledge is a double-edged sword. On one hand knowledge is the greatest tool we have for understanding the world in which we live.

The knowledge we possess makes up the raw material for everything we think; it’s an essential component of all our ideas, our decisions, our problem solving and our creativity.

When it is allowed to be fluid and ever evolving knowledge is exciting and inspiring, and leaves us craving more.

The Tyranny of Knowledge

Yet, at some point, knowledge can do just the opposite. It can become the very thing that holds us back.

As we grow complacent and comfortable in our knowledge it becomes stale and our brains grow lazy.

When our brains say to us “I know! There’s no need to look further”, we stop questioning and become willing submissives to the tyranny of knowledge.